by Lieve Orye

Several treads of thought woven at the conference in 2016 have been rewoven into paper and digital format. A Louvain Studies issue has been published recently with contributions of several keynote speakers and respondents. Under the menu heading ‘Special issue Louvain Studies 2018’ you can find a table of contents and links to further information.

As editors, Yves de Maeseneer and I feel that this special issue has become a well-woven cloth, a colorful tapistry of thought and reflection on the what and how of theological anthropology in the 21st century. We particularly would like to draw attention to the last article in this issue, ‘Weaving Theological Anthropology into Life. Editorial Conclusions in Correspondence with Tim Ingold’. In this last contribution, we weave together five key themes that have been raised in the different contributions of this issue, and we do so in conversation with the work of anthropologist Tim Ingold. This weaving together confirms the terms ‘relation’, ‘vulnerability’ and ‘love’ as key for theological anthropology in the twenty-first century.

A first theme is theological anthropology’s conversation with the discipline of anthropology. The first section addresses Michael Banner’s call for a more thorough anthropological turn for theological anthropology. Following a line of connection starting from anthropologist Joel Robbins, who has inspired Banner in taking this turn, towards Ingold, we argue that the latter’s understanding of anthropology as ‘philosophy with the people in’ turns him into a much more interesting conversation partner for a theological anthropology that wishes to pay attention to the work of being human and being moral ‘on the ground’.

The second section finds a similar opening for conversations between theology and anthropology in relation to evolutionary perspectives. Here we make the connection with anthropologist Agustín Fuentes’ work in order to open up such a space. Fuentes does important work, as both Jan-Olav Henriksen and Markus Mühling appreciate. But, we argue here again – in line with Mühling’s contribution – that Ingold’s reflections in conversations with evolutionary theorizing take us onto a fundamentally different path towards a fully relational theological anthropology.

A second theme is woven through these first two sections. Being human is a practice, notes Banner. Or, as Brian Brock indicates with the help of Barth, we exist in our acting. In Ingold’s relational anthropology ‘to human’ is a verb; being human is a never-ending task. In these understandings, a perspective that sees knowing-in-being as primary is indicated. We argue with Ingold that Henriksen’s emphasis on what is specifically human is important to keep, though within a framework that goes beyond a human-animal and a culture-biology divide by prioritizing movement and life in a forward-going approach.

The third and fourth themes, addressed in the third and fourth sections, must be seen, with Ingold, as two sides of the same coin. The third theme involves a weaving together of Ingold’s primacy of knowing-in-being with Banner’s and Brock’s existing-in-believing. This further opens up a discussion of enskilment, of tradition and way-formation, and of imagination and vision in a relational, participative perspective.

The fourth theme, however, clarifies with the help of Elizabeth Gandolfo and Paul Fiddes that such knowing-in-being fundamentally involves exposure and existential risk in a ‘wild’ world. Vulnerability surfaces as a key notion here. We follow Ingold in taking a step beyond James Gibson’s ecological psychology which was key in Mühling’s contribution, towards an understanding of the world, not as a given, but always on its way to being given.

The fifth theme brings us to theology’s areas of concern in the conversation with anthropology. Theology ‘from a wound’ points to the dark side of wildness and vulnerability, and to the need to discern when and how to embrace or to resist vulnerability. Importantly, such discernment and resistance happen through existing-in-believing: precisely a believing and acting that discovers through participation that love is the deepest reality.

As organizers of the conference and as editors of this Louvain Studies issue, we would like to thank once more everyone who in one way or another made a contribution. We hope that several of the threads of thought and reflection developed and woven together at the conference, in the blog (easily accessible through the previous blogpost) and in the journal issue will find further life, growing into further thoughts, comingling with other lines, taking up other forms and shapes. But even more, we hope that these threads of thought might find ways to correspond and comingle with lines of life, nurturing these towards a more sustainable world. Our hope is that theological anthropology in the 21st century will be a discipline with a critical agenda, in line with Joel Robbins’ characterization of theology and anthropology as critical disciplines nourished by O/otherness, and that, in line with Tim Ingold’s characterization of anthropology, it becomes shaped by a method of hope.

Relation, vulnerability, love

For those of you who would like to explore the previous blogs chronologically, below you find an overview. The blog posts, with excerpts from the keynote speakers, respondents and other relevant authors, show a richly textured subject matter, which you can easily access through the categories-list. We also would like to draw attention to the contributions from Jacques Baeni Mwendabandu and Gakwaya Remy, both residents in Dzaleka Refugee Camp, Malawi. Through skype they were directly involved in a session at the conference.

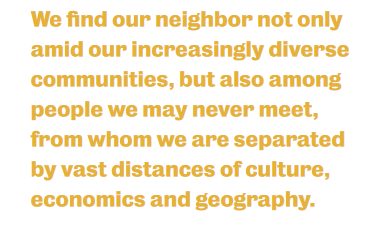

For those of you who would like to explore the previous blogs chronologically, below you find an overview. The blog posts, with excerpts from the keynote speakers, respondents and other relevant authors, show a richly textured subject matter, which you can easily access through the categories-list. We also would like to draw attention to the contributions from Jacques Baeni Mwendabandu and Gakwaya Remy, both residents in Dzaleka Refugee Camp, Malawi. Through skype they were directly involved in a session at the conference. Loving our suffering neighbor in an age of globalization entails the ability to perceive self-critically both ourselves and our connections as the causes of others’ suffering. (…) Several values wreak emotional havoc on first-world persons and hinder us in responding to others in need on the road to Jericho. For example, individualism isolates us from others, self-sufficiency rejects vulnerability, consumerism creates an anxious insatiability, competitiveness pits social ‘winners’ against ‘losers’, and fear perpetuates a defensive posture toward the world. (…)

Loving our suffering neighbor in an age of globalization entails the ability to perceive self-critically both ourselves and our connections as the causes of others’ suffering. (…) Several values wreak emotional havoc on first-world persons and hinder us in responding to others in need on the road to Jericho. For example, individualism isolates us from others, self-sufficiency rejects vulnerability, consumerism creates an anxious insatiability, competitiveness pits social ‘winners’ against ‘losers’, and fear perpetuates a defensive posture toward the world. (…) a deeper concern for those who experience it more acutely than others. It cultivates the value of deep relationality with others that motivates us to embrace rather than avoid the dangers and mysteries of difference. It values the messiness and beauty of human embodiment so that we risk asking people how they actually experience different strategies of development – physically and emotionally – and not just safely seek perspective of other privileged persons. (…)

a deeper concern for those who experience it more acutely than others. It cultivates the value of deep relationality with others that motivates us to embrace rather than avoid the dangers and mysteries of difference. It values the messiness and beauty of human embodiment so that we risk asking people how they actually experience different strategies of development – physically and emotionally – and not just safely seek perspective of other privileged persons. (…)

Refugees and asylum seekers face many challenges in their everyday life. Even though humanitarian organizations provide assistance, they cannot replace properly the comfort which refugees had in their home countries. Comparing life in the home country to life in a refugee camp, it seems that living in the camp feels much like living in a prison. In fact the Dzaleka facilities, the accommodation where I stay as a refugee in Malawi, had served as a political prison in the past. It was established as a refugee camp by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1994.

Refugees and asylum seekers face many challenges in their everyday life. Even though humanitarian organizations provide assistance, they cannot replace properly the comfort which refugees had in their home countries. Comparing life in the home country to life in a refugee camp, it seems that living in the camp feels much like living in a prison. In fact the Dzaleka facilities, the accommodation where I stay as a refugee in Malawi, had served as a political prison in the past. It was established as a refugee camp by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 1994. ross, the moment they are no longer refugees, their time of salvation, or perhaps more appropriately, of resurrection. Leaving the camp is their daily prayer. For them, the third country is the Promised Land. Others pray God to help them to speed up their social integration in the host country as citizens. But refugees and asylum seekers observe that God’s response to their suffering takes too long. Even though living in a refugee camp is painful and temporary, refugees live a real life. Some are born in the camp. Some get married there. Others find their faith in the camp, while others live bad lives. Waiting for relief, they wonder whether God will deliver some of these people.

ross, the moment they are no longer refugees, their time of salvation, or perhaps more appropriately, of resurrection. Leaving the camp is their daily prayer. For them, the third country is the Promised Land. Others pray God to help them to speed up their social integration in the host country as citizens. But refugees and asylum seekers observe that God’s response to their suffering takes too long. Even though living in a refugee camp is painful and temporary, refugees live a real life. Some are born in the camp. Some get married there. Others find their faith in the camp, while others live bad lives. Waiting for relief, they wonder whether God will deliver some of these people.

That clock tower on Amatrice church indicating 3:36 am is a powerful image for what happened this night. That minute was the last minute for many victims, it will be a minute forever remembered because it is written in the flesh and hearts of their families. And it will be remembered by our country, whose recent history is also a series of clocks stopped forever by the violence of men and of the earth. I will also remember it forever, because this cry of the earth also reached the house of my parents in Roccafluvione, around twenty kilometres from Arquata del Tronto, where I am visiting them. It was a long night of fear, suffering and thoughts for Amatrice, Arquata, Accumuli, towns of my childhood, close to where my grandparents come from, villages where I would accompany my father as he went about his business selling chickens. And then there were thoughts, thoughts we never have, because you can only have them on these terrible nights.

That clock tower on Amatrice church indicating 3:36 am is a powerful image for what happened this night. That minute was the last minute for many victims, it will be a minute forever remembered because it is written in the flesh and hearts of their families. And it will be remembered by our country, whose recent history is also a series of clocks stopped forever by the violence of men and of the earth. I will also remember it forever, because this cry of the earth also reached the house of my parents in Roccafluvione, around twenty kilometres from Arquata del Tronto, where I am visiting them. It was a long night of fear, suffering and thoughts for Amatrice, Arquata, Accumuli, towns of my childhood, close to where my grandparents come from, villages where I would accompany my father as he went about his business selling chickens. And then there were thoughts, thoughts we never have, because you can only have them on these terrible nights. The earth, the real one and not the romantic and naive one of ideologies, is both mother and stepmother. The hummus generates man but also turns him back into dust, sometimes in a good way at the right time, but other times it is bad, and too soon, with a so much suffering. Biblical humanism knows this very well, but for this has fought a lot with the pagan cults of local peoples who wanted to make a divinity of the earth and its nature: the power of the earth has always fascinated men who have tried to ‘buy’ it with magic and sacrifices. Whilst I tried in vain to go back to sleep, I thought about the tremendous books of Job and Qohelet, which you can understand on such nights. Those books tell us that no God, not even the real one, can control the earth, because He too, once he entered into human history, became a victim of the mysterious freedom of his creation.

The earth, the real one and not the romantic and naive one of ideologies, is both mother and stepmother. The hummus generates man but also turns him back into dust, sometimes in a good way at the right time, but other times it is bad, and too soon, with a so much suffering. Biblical humanism knows this very well, but for this has fought a lot with the pagan cults of local peoples who wanted to make a divinity of the earth and its nature: the power of the earth has always fascinated men who have tried to ‘buy’ it with magic and sacrifices. Whilst I tried in vain to go back to sleep, I thought about the tremendous books of Job and Qohelet, which you can understand on such nights. Those books tell us that no God, not even the real one, can control the earth, because He too, once he entered into human history, became a victim of the mysterious freedom of his creation. The liberationist method highlights, on the one hand, critical social analysis and, on the other, the choice of structurally marginalised people as interlocutors. The condition of truth, …, then necessitates identifying those who suffer and allowing them a space to speak. To allow someone to speak, in turn, requires the skill to listen, and to do so ethically.(p.196)

The liberationist method highlights, on the one hand, critical social analysis and, on the other, the choice of structurally marginalised people as interlocutors. The condition of truth, …, then necessitates identifying those who suffer and allowing them a space to speak. To allow someone to speak, in turn, requires the skill to listen, and to do so ethically.(p.196) Excerpt from Oliver Davies’ chapter ‘Neuroscience, Self and Jesus Christ’, published in Questioning the Human. Towards a Theological Anthropology for the Twenty-First Century, edited by Lieven Boeve, Yves de Maeseneer and Ellen van Stichel, Fordham University Press, 2014, pp.89-90.

Excerpt from Oliver Davies’ chapter ‘Neuroscience, Self and Jesus Christ’, published in Questioning the Human. Towards a Theological Anthropology for the Twenty-First Century, edited by Lieven Boeve, Yves de Maeseneer and Ellen van Stichel, Fordham University Press, 2014, pp.89-90.